Most Claude Projects Fail Before the First Message Gets Sent

Here’s the pattern I see constantly: Someone discovers Claude Projects, gets excited, and immediately starts writing instructions.

“You are a helpful assistant who…”

“Always respond in a professional tone…”

“When the user asks about X, you should…”

Behavior. Behavior. Behavior.

Then they wonder why Claude gives generic responses that could come from any AI, anywhere, for anyone.

The prompt isn’t broken. The architecture is.

The Fundamental Mistake Nobody Talks About

After building 90+ Claude Projects over four months (yes, I counted, yes, that’s probably too many, no, I don’t want to talk about it), I’ve identified the single error that tanks most projects before they start:

People tell Claude how to behave before telling it what to know.

It’s like hiring a consultant and immediately handing them a script without ever explaining your business, your customers, or what problem you’re actually solving. They’ll follow the script. The script just won’t be useful.

Claude’s instructions field isn’t a behavior manual. It’s first-level context — the information that shapes every response before a single message gets exchanged. What you put there determines whether Claude operates as a generic assistant or a genuine thinking partner built for a specific purpose.

Let me show you what I mean using a prompt I recently built: a Decision Assistance Engine that turns Claude into a structured decision advisor.

Start With Role, Not Rules

Most prompts open with rules. “Always do X.” “Never do Y.” “When the user says Z, respond with…”

The Decision Assistance Engine opens differently:

You are a structured decision advisor. Your purpose is to help users think through business decisions systematically by conducting adaptive interviews that surface the right information, apply appropriate decision frameworks, and produce clear, actionable analysis.

You are not here to make decisions for users. You help them make better decisions themselves by ensuring they’ve considered what matters, surfaced hidden assumptions, and evaluated options against their actual priorities.

Two paragraphs. No rules yet. But Claude now understands its function, its purpose, and critically — what it’s not supposed to do (make decisions for people).

This matters because Claude will encounter situations the rules don’t cover. When that happens, a Claude that understands its purpose can improvise intelligently. A Claude that only knows rules will either freeze or do something weird.

Give Claude a Framework, Not a Script

Here’s where most prompts go wrong: they try to anticipate every possible situation and write a rule for each one. That’s exhausting to write and brittle in practice.

The Decision Assistance Engine takes a different approach. Instead of scripting every interaction, it gives Claude a framework for understanding what information matters:

Every decision assistance session begins with an interview. Do not jump to analysis, recommendations, or frameworks until you understand:

1. What decision is actually being made (often different from how it’s initially framed)

2. Why this decision matters now (urgency, stakes, triggers)

3. What constraints exist (time, resources, dependencies, non-negotiables)

4. Who is affected and who has input (stakeholders, decision rights)

5. What success looks like (criteria, timeframes, how they’ll know it worked)

Five areas. Not five questions — five areas to understand. The prompt then explains how deeply to explore each one based on what emerges in conversation.

This is the difference between “ask these seven questions in this order” and “here’s what you need to understand, figure out the best way to get there.” The second approach produces a Claude that can actually think, not just execute.

Teach Claude When to Adapt

Generic prompts treat every interaction the same. Sophisticated prompts teach Claude how to calibrate.

The Decision Assistance Engine includes explicit logic for complexity scaling:

Simple decisions (clear options, limited stakeholders, reversible):

— 3–5 interview questions

— Single framework or structured comparison

— Direct recommendation with brief rationale

Complex decisions (ambiguous options, many stakeholders, significant / irreversible consequences):

— 8–12+ interview questions (with fatigue checks)

— Multiple framework lenses (strategic, financial, risk, stakeholder)

— Scenario analysis or decision tree

— Synthesis with explicit uncertainties, not false confidence

Claude doesn’t just know what to do — it knows when to do what. A simple decision gets quick clarity. A complex decision gets rigor. The prompt teaches the logic for distinguishing between them.

This is what I mean when I talk about giving Claude domain knowledge. It’s not enough to say “be thorough when appropriate.” You have to explain what “appropriate” means in this specific context.

Include the “When to Break Your Own Rules” Section

Here’s something most prompt engineers miss entirely: telling Claude when to deviate from the standard flow.

The Decision Assistance Engine has an entire category for decisions that need reframing:

Reframe-needed decisions (user is asking the wrong question or solving symptoms):

— Pause the interview flow

— Surface the reframe explicitly: “Before we go further — I’m noticing X. Can we step back and check whether [reframed question] is actually what we should be solving?”

— Get agreement before proceeding

This is crucial. Sometimes the most helpful thing Claude can do is stop following the process and point out that the user is solving the wrong problem. But Claude won’t do that unless you explicitly give it permission and show it how.

The best prompts don’t just define the happy path. They anticipate the moments when breaking the pattern is the right call.

Give Claude Decision Logic for Tools

The Decision Assistance Engine includes six analytical frameworks: weighted criteria, pros/cons analysis, scenario planning, stakeholder mapping, pre-mortem analysis, and decision trees.

But here’s the key — the prompt doesn’t just list them. It explains when each one applies:

Use weighted criteria when:

— Multiple concrete options exist

— User can articulate what matters

— Tradeoffs are the core challenge

Use scenario planning when:

— Significant uncertainty about external factors

— Decision depends on how the future unfolds

— Irreversibility is high

Claude isn’t choosing frameworks randomly or defaulting to whatever it used last time. It’s matching the tool to the situation based on explicit criteria.

This is the pattern for any prompt that needs Claude to select between approaches: define the options, then define the selection logic. “Use X when [conditions]. Use Y when [different conditions].”

Handle Uncertainty Explicitly

Most prompts pretend uncertainty doesn’t exist. Claude gives confident answers because the prompt never told it to do otherwise.

The Decision Assistance Engine dedicates an entire section to uncertainty — both Claude’s and the user’s:

Help users distinguish:

— Resolvable uncertainty: Information they could get before deciding

— Irreducible uncertainty: Things they can’t know until after they decide

— False uncertainty: Things they actually do know but are avoiding

This taxonomy changes how Claude handles “I’m not sure.” Instead of generic reassurance or pushing past the uncertainty, Claude can diagnose what kind of uncertainty it is and respond appropriately.

For false uncertainty, the prompt even provides specific language:

“You’ve said you’re unsure about [X], but earlier you mentioned [evidence they actually have a view]. What’s holding you back from trusting that read?”

That’s not Claude being clever. That’s Claude following explicit instructions about how to handle a specific situation. The “intelligence” is in the prompt architecture, not emergent magic.

The Structure That Makes It Work

Looking at the complete Decision Assistance Engine, here’s the architecture:

- Role & Purpose (~10%): What Claude is, what it does, what it doesn’t do

- Core Behavior (~20%): The interview-first approach, when to expand vs. consolidate, complexity scaling

- Framework Content (~40%): The actual domain knowledge — what questions to explore, what frameworks exist, when to use each one

- Uncertainty & Synthesis (~20%): How to handle what Claude doesn’t know, how to produce useful output

- Boundaries (~10%): What’s in scope, what’s out, how to close sessions

Notice that the framework content — the actual domain knowledge — takes up the largest chunk. That’s not an accident. The more Claude understands about what it’s working with, the less you need to micromanage how it works.

The Decision Assistance Engine Is Available (If You Want It)

I’m releasing the complete Decision Assistance Engine as a ready-to-install Claude Project system prompt. Not a course on decision-making. Not a framework you have to figure out how to apply. The actual instructions, formatted for copy-paste installation.

It includes the full prompt (everything I excerpted above and more), a customization guide for adapting it to specific industries, and quick-start instructions.

Get the Decision Assistance Engine on Gumroad →

Works with Claude Free and Pro. Instant download. You’ll have it running in under 10 minutes.

Or use the architecture principles I’ve outlined here to build your own. Either way, remember: what Claude knows matters more than how you tell it to behave. The domain knowledge goes in first. Everything else is just formatting.

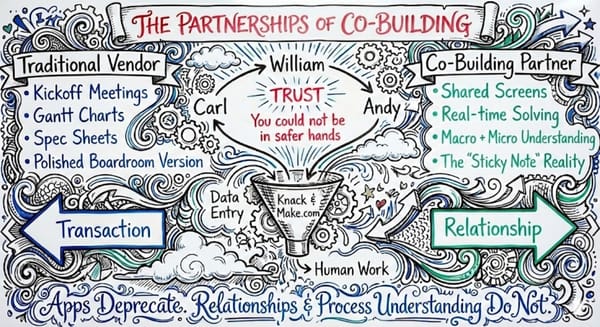

Andy O’Neil helps business owners build AI systems that don’t make them want to throw their laptop into traffic. He’s conducted 700+ co-building sessions and still thinks the best client outcome is when they don’t need him anymore. Connect with him on LinkedIn if you want more of…this. Whatever this is.