I Built 80 Claude Projects in 4 Months. The First 20 Were Garbage.

Here’s something they don’t tell you about Claude projects: you can be very, very good at prompting and still build junk projects.

Here’s something they don’t tell you about Claude projects: you can be very, very good at prompting and still build projects that end up collecting digital dust next to that meditation app you downloaded in January.

I know this because I’ve created 80 Claude projects in the past four months. Not for clients. For myself. Personal R&D. The kind of obsessive tinkering that makes my family exchange concerned glances across the dinner table.

The first twenty or so? Absolute disasters. Beautiful, well-intentioned disasters — like a Pinterest craft project that looked amazing in the photo and ended up as a sticky mess on the kitchen counter. I’d open them once, realize they required more setup than just asking Claude directly, and quietly pretend they never existed.

But somewhere around project twenty-five, something clicked. I stopped building projects like enhanced chat windows and started building them like… well, like actual infrastructure. And now I have a three-step system that would have saved me approximately forty hours of my life and one minor existential crisis about whether I actually understand AI at all.

The Mistake Everyone Makes (Including Me, Repeatedly)

When you create a new Claude project, you get this beautiful blank field called “Instructions.” And something about that blank field activates the same part of your brain that sees an empty whiteboard and thinks, “I should write a manifesto.”

So you start typing. You explain your business. Your communication style. Your preferences. That thing you always want Claude to remember. The specific way you hate when AI uses the phrase “dive into.” Before you know it, you’ve written 2,000 words of instructions that essentially say “be helpful in my general direction.”

This feels productive. It is not productive. It is the productivity equivalent of reorganizing your sock drawer when you have a deadline.

I built SO MANY of these projects. “Andy’s Marketing Helper.” “Content Strategy Assistant.” “Email Wizard Pro.” (I didn’t actually name one “Email Wizard Pro” but I absolutely would have if I’d thought of it, because past-Andy had no shame.)

Every single one followed the same trajectory: excitement, first use, mild disappointment, second use with lowered expectations, abandoned forever.

The problem wasn’t Claude. The problem was that I was trying to create a personality when I should have been building a machine.

The One-Outcome Rule (Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Constraints)

Somewhere around my thirtieth project failure, I had a realization that felt embarrassingly obvious in retrospect: good projects produce one specific thing.

Not “help with marketing.” Not “assist with client communication.” One. Specific. Outcome.

A project that takes any article and produces three LinkedIn post variations. A project that transforms meeting notes into structured action item lists. A project that analyzes competitor websites and outputs a standardized intelligence brief.

One input type. One output type. Infinite reuse.

The beautiful paradox — and I really do mean beautiful, in the way that a perfectly organized spreadsheet is beautiful, which I recognize is a concerning thing to find beautiful — is that constraining your project to one outcome makes it MORE flexible, not less.

When Claude knows exactly what it’s supposed to produce, it can handle wildly different inputs. Paste in a blog post, get LinkedIn variations. Paste in podcast notes, get LinkedIn variations. Paste in your competitor’s about page while feeling vaguely like a spy, get LinkedIn variations.

Same outcome every time. That’s not a limitation. That’s the whole point.

The Three-Step System (That I Wish Someone Had Told Me About 40 Hours Ago)

After building approximately too many mediocre projects, I figured out that the instructions field isn’t one thing. It’s actually two completely different things pretending to be roommates.

Thing One: Domain knowledge. What does this project need to understand about the world? What context, research, and expertise should inform the outputs?

Thing Two: Behavioral rules. How should outputs be structured? What format? What tone? What should always be included or excluded?

Most people — including past-Andy, who I’m increasingly irritated with — mash these together into one blob of instructions. They write detailed rules for outputs without giving Claude any actual expertise to apply those rules to. It’s like giving someone a very specific style guide for a job they weren’t trained for.

“Make it professional but approachable, use headers, include actionable takeaways” means nothing if Claude doesn’t understand the domain deeply enough to know WHAT should be approachable or which takeaways actually matter.

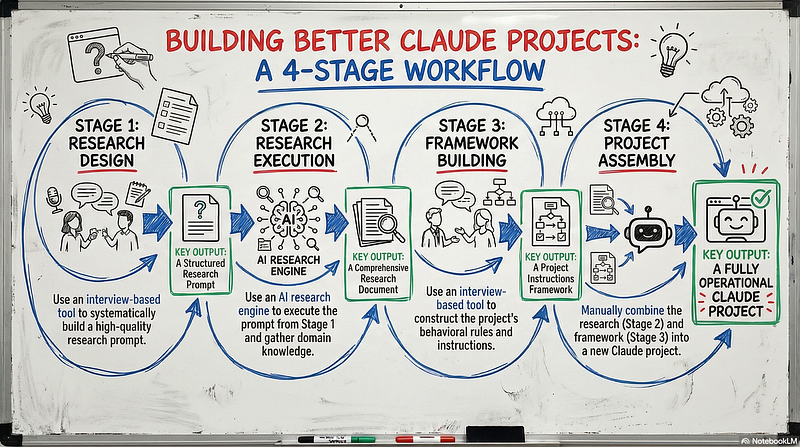

So here’s the three-step system that would have saved me from myself:

Step One: Research Design. Before you write a single instruction, figure out what domain knowledge this project needs. What does Claude need to deeply understand for this outcome to be good? Not “marketing” — that’s too vague. What specifically? Content strategy for B2B SaaS? Competitive positioning in the aesthetics industry? The specific regulatory landscape for your niche?

Step Two: Research Execution. Actually gather that knowledge. Do the research. Compile it. This becomes the expertise layer of your project — the stuff Claude knows about the domain that makes its outputs actually intelligent instead of generically plausible.

Step Three: Framework Building. NOW you write behavioral instructions. Structure, format, tone, boundaries. But you’re writing these rules for a Claude that already has domain expertise, not a blank slate that’s going to wing it.

Research first. Behavior second. Always in that order.

This is the part where younger-Andy yells from the void: “BUT THAT TAKES LONGER!” Yes. It does. It takes maybe 30 minutes instead of 10. And then you actually use the project instead of abandoning it after two days. Math is fun when you include the opportunity cost of building garbage.

The Project Instructions Are the Brain (So Maybe Don’t Lobotomize It)

Here’s a metaphor that’s either illuminating or deeply weird, depending on how you feel about comparing software to neurology.

The instructions field is the project’s brain. It’s not a settings menu. It’s not a preferences panel. It’s the actual cognitive architecture that determines whether your project produces genius or word salad.

When you skip the research step, you’re essentially building a brain with no knowledge — just rules about how to behave. That’s not a brain. That’s a very organized empty room.

When you skip the behavioral rules, you’re building a brain full of knowledge but no structure for applying it. That’s not a brain either. That’s my browser tabs situation at 11 PM on a Tuesday.

You need both. And you need them designed intentionally, not stream-of-consciousness typed while you’re also half-watching a YouTube video about productivity. (I have never done this. I have done this many times.)

The Reusability Test (A.K.A. The “Would I Actually Use This 50 Times?” Gut Check)

Here’s how you know if a project is going to survive contact with your actual workflow: imagine using it fifty times.

Not once. Not in the demo where everything works perfectly and you briefly feel like a genius. Fifty times over the next three months.

Does each use require you to re-explain context? Problem.

Does the output need editing before it’s usable? Problem.

Do you have to remember special instructions that aren’t baked into the project? Believe it or not, also problem.

A project that passes the fifty-use test feels almost boring to operate. Input goes in, useful output comes out. No cleverness required on your part because you front-loaded all the cleverness into the system.

This is the goal. Not impressive on first use. Invisible on fiftieth use.

When Projects Should Stay Stupid

Not everything needs to be sophisticated. Some of my most-used chat conversations aren’t projects at all. They are just one-time chats.

One just reformats meeting notes into a specific template. That’s it. That’s the whole project. A trained golden retriever could probably do it if golden retrievers had keyboards and understood markdown.

Another extracts action items from any text and lists who’s responsible for what. Not exactly pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence.

But you know what these projects do? They get used. Daily. Because the value isn’t in complexity — it’s in removing decisions. Every time I don’t have to think “how should I format this,” I’ve saved myself a tiny cognitive paper cut. Those paper cuts add up.

If you’re over 40, imagine finally setting the clock on your VCR so it stops blinking 12:00. That permanent relief. That’s what a good Claude project feels like. If you’re under 40, ask your parents about the emotional trauma of blinking VCR clocks. There’s generational healing to be done.

The Uncomfortable Truth About My First 20 Projects

Those early projects I built weren’t bad because I’m bad at AI. They were bad because I skipped the boring parts.

I didn’t want to spend twenty minutes thinking about what the project actually needed to know. I wanted to jump straight to the fun part — writing clever instructions that made me feel like I was accomplishing something.

But clever instructions for an unclear outcome just produce articulate confusion. You get outputs that sound good and aren’t useful, which is somehow worse than outputs that are obviously broken.

The projects I actually use every day? The ones I built after I started doing research first and behavior second? They’re not particularly clever. They’re clear. They know one thing deeply. They produce one outcome reliably.

That’s it. That’s the whole secret. Eighty projects and one mildly obsessive four-month journey to figure out something that probably should have been obvious from the start.

One outcome. Domain knowledge first. Behavioral rules second.

Everything else is just making your robot assistant work harder than it needs to while you pretend you’re being productive.

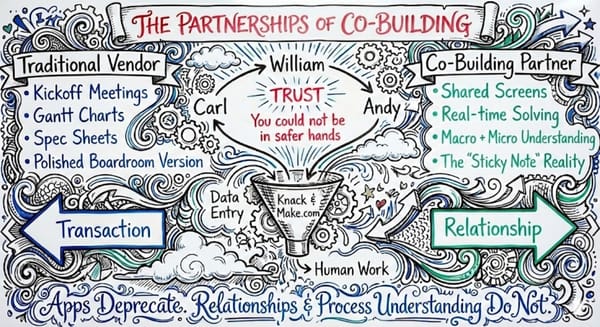

Andy O’Neil helps business owners build AI systems that don’t make them want to throw their laptop into traffic. He’s conducted 700+ co-building sessions, built 80 Claude projects for himself (the first 20 were learning experiences, which is a polite way of saying “garbage”), and still thinks webhooks are basically magic. Connect with him on LinkedIn if you want more of… this. Whatever this is.