Get a Real Job

What Twelve Years of Freelancing Taught Me About Survival, Reinvention, and Knowing Who You Are

Seven days before Christmas in 2012, my boss Skyped me to ask if I could come into the office the next day. I’d planned to take it off, but she said there was a meeting I needed to attend.

So I came in. Khakis, dress shirt. The meeting was her telling me I was fired.

I actually came into work special for my own firing. I still think about that.

The job was supposed to be perfect. It combined my two areas of expertise — agriculture and technology — into one role. I’d moved my family to Kansas City for it. I believed in it.

What I didn’t expect was the isolation.

We sat in cubicles but communicated almost entirely through Skype. No water cooler talk. No lunch invitations. I’d send a message to my boss or a colleague — someone I knew was sitting fifteen feet away, not on the phone, definitely at their desk — and it would just sit there. No response. Minutes passing. It felt like punishment by waiting. Punishment for asking a stupid question, or for doing something wrong, or just for existing in a space where I clearly wasn’t wanted.

I remember asking a colleague if he’d booked his flights for an upcoming business trip. First time I’d be traveling with the company. I thought maybe we could coordinate, fly together.

“I already booked my flights,” he said.

That was it. No details. No offer to share when he was leaving. Just a wall.

My boss was a grad school friend who had become something else entirely. Every mistake I made — and I made plenty — got documented. She spent more time building a case against me than she ever spent helping me learn the job. We’d have these “gap analysis” meetings where she’d bring worksheets with fill-in-the-blank questions about my feelings and my performance.

I made the mistake once of telling her it reminded me of Sunday school worksheets from when I was a kid. She did NOT take that very well.

I’m an ISTP. The last thing I want to do is fill in blanks about my emotions. The whole setup was designed for a brain that wasn’t mine.

By the end, I felt guilty taking bathroom breaks. I felt guilty leaving at 5:25, which was apparently the “okay time” to leave — except my boss accused me of clock-watching because I always left right at 5:25. She wanted me to stay until 5:35 or 5:45 or later, like everyone else seemed to. But I had a wife and kids at home, and I just wouldn’t.

Clock-watching. That’s what she called it. I called it having a family.

When they let me go, they paid me through the end of the year. My boss said that never happens. I think she was trying to be kind. Honestly? I was relieved. Tired of the place. It was a release to finally pack my box and leave.

A year and five months later, I got let go again.

Operations manager at a nonprofit. Good people, meaningful work. But the money ran out, and when it did, so did my job.

My wife, in what I now lovingly call “a moment of weakness,” agreed to let me try freelancing.

She was scared. I was scared. Neither of us had any idea what we were doing.

What followed was months of phone calls to my mom asking for money. I always called her instead of my dad — she was easier to talk to about these things. My wife and I would go over the books together, see the gap, and then I’d go down to my office alone and make the call.

Same spot every time. Hiding away to have the hard conversation.

I’d beat around the bush for a minute, and Mom would cut through it: “How much do you need?”

I’d tell her. She’d say yes. And we’d try again for another month.

There was shame in those calls. The specific shame of being a grown man who can’t provide for his family. And gratitude when she said yes, because it meant I got another shot.

One afternoon, about five minutes after hanging up with her, my phone buzzed.

Text from dad: “Time to get a real job.”

He knew. She’d told him. It wasn’t coordinated — just terrible timing.

I sat there. Shook my head. Put the phone down on my desk.

I didn’t respond. There was nothing I could say that would help the situation.

I told my wife. She was pretty upset. But I tell her everything.

I started applying for jobs. Real ones. The kind with benefits and predictable paychecks.

And then I got a call.

Someone I’d cold-pitched weeks earlier. A nonprofit. They wanted me two and a half days a week — some on-site, some remote.

I said yes.

Within days, another call. A regional radio station. Three days a week.

That’s more than full-time. Suddenly. Out of nowhere.

I was overwhelmed. I’d never written a contract before. I didn’t know how to handle any of this.

But the guy at the nonprofit — Adrian — asked how I was doing with the logistics. I admitted I had no idea what I was doing.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s work on it together.”

No judgment. No worksheets. Just someone willing to walk alongside me while I figured it out.

I didn’t have to get a real job after all.

That was 2014.

In 2017, I discovered an automation tool called Integromat — now Make.com. Something about the logic of connecting systems clicked with how my brain works. By 2019, I was doing live Zoom calls helping other users learn to build their own automations. I called it “Premium Integromat Support” and started a YouTube channel to promote it.

Call after call after call.

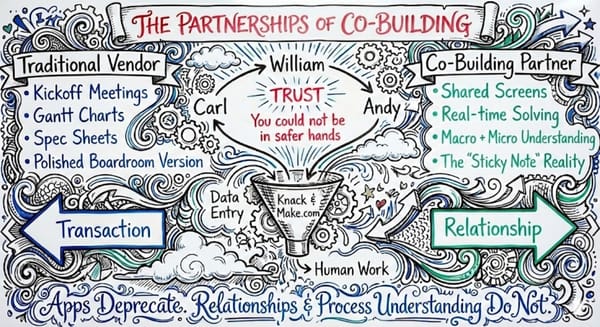

Somewhere around 2021, while I was updating my website for Integromat’s rebrand to Make, I realized something. What I’d been doing on those calls wasn’t support. I wasn’t just answering questions. I was building alongside people. Working with them, not for them.

I started calling it co-building.

Over 700 hours now. Businesses and industries I never imagined I’d touch. One client runs senior expos across the North Central U.S. — used to do wedding expos, pivoted to seniors. Multiple events at once, different cities, different managers, whole sales team.

Who grows up saying they want to be a senior expo coordinator? Apparently somebody does. And his automations needed building.

If this were a different kind of story, this is where I’d tell you I made it.

But about a year ago, a competing tool started gaining traction. A lot of people I’d worked with left Make for n8n. My income dropped.

I’ve pivoted toward building AI systems now — personalized assistants for executives, trained on their communication style and personality type. Work I believe in.

But there’s so much noise in the AI space. So much hype. Getting the right people to understand what I’m offering has been slow.

I’m not struggling like I was in 2013. I have experience now. Clients who’ve stuck with me for years. People I can call.

But I am reinventing myself. Again.

Someone reading this might be five minutes past their own “get a real job” text. Wondering if they’re foolish for trying.

I’d say probably not. But know yourself first.

If the work you’re pursuing doesn’t match how you’re wired — if your personality type reads like a completely different person than the job requires — pivot fast. I spent months in a role that required me to process emotions through fill-in-the-blank worksheets. I’m an ISTP. That was never going to work.

The market will tell you if you’re listening. I’ve watched freelancers declare their independence and take jobs six months later. Not failure — just not a market fit. They wanted to offer X when the market needed Z.

Freelancing isn’t a thing you figure out and then you’re done. It’s cycles. You find something that works, you ride it, and then the ground shifts (or violently shakes) under your feet. What changes isn’t whether you’ll have to reinvent yourself. What changes is whether you believe you can.

I’ve got too much grit to quit. If I’m not doing well, I try harder. Double down. Do something different. Ask somebody what to do.

After twelve years, I know who I am. I know my gifts. I know there’s a place for me to help people — even if I have to find them again, even if the tools and the market look nothing like they did a decade ago.

That’s the thing I couldn’t have known in 2013, sitting there after my dad’s text.

I know it now.

About the Photo: The photo above is two seedlings — one a little further along than the other. That’s co-building. That’s what Adrian did for me in 2014. That’s what I try to do now. You don’t have to be an expert. You just have to be a few steps ahead and willing to stand in the same dirt.

Photo Credit: Image created by author using Google Gemini

Andy O’Neil started his career teaching agriculture. Now he builds automation and AI systems — but he’s still teaching. After twelve years of freelancing, he’s learned that “figuring it out” is the job, not the prerequisite. Connect with him on LinkedIn.