5 Things I Learned After Building 80 Claude AI Projects (That I Wish I’d Known After Building 5)

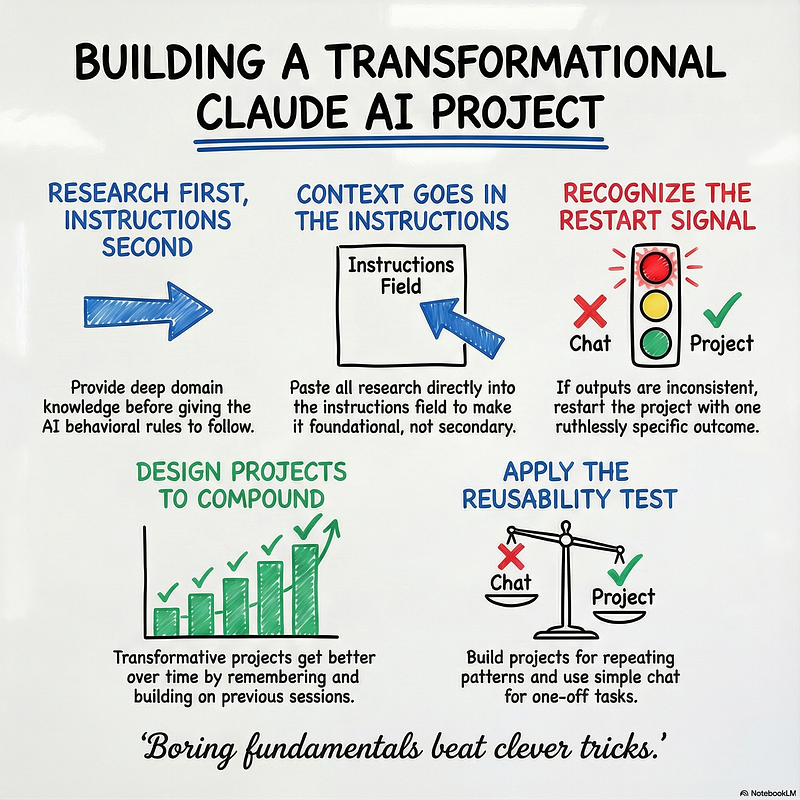

Eighty projects taught me that the boring fundamentals matter more than clever tricks. Research before instructions. One outcome per project

I have a problem.

Over the past four months, I’ve built 80 Claude projects. Not for clients. For myself. The kind of relentless experimentation that makes my wife ask “are you okay?” in a tone that suggests she already knows the answer.

The first twenty or so were educational experiences, which is a polite way of saying they were garbage. Beautiful, well-intentioned garbage — like a New Year’s resolution that sounds great on January 1st and becomes a punchline by January 4th.

But somewhere in the wreckage of those early failures, patterns started emerging. Things that consistently worked. Things that consistently didn’t. The kind of observations you can only get from doing something slightly too many times.

Here are five of them.

1. Projects Without Research Are Just Fancy Chat Windows

My first twenty projects all had the same problem: I tried to write instructions from scratch.

I’d open that beautiful blank instructions field, crack my knuckles like a pianist about to perform, and start typing. My communication preferences. My business context. The specific way I wanted outputs formatted. All the clever rules I’d accumulated from months of prompting.

And then I’d use the project once, get mediocre results, and quietly abandon it like a gym membership in February.

The issue wasn’t the instructions themselves. The issue was that I was giving Claude behavioral rules without giving it any actual expertise to apply those rules to. “Be professional but approachable” means nothing if Claude doesn’t deeply understand the domain. “Include actionable takeaways” is useless guidance when there’s no knowledge foundation to draw takeaways FROM.

The projects that actually work — the ones I use daily — all started with research. Not “I’ll figure it out as I go” research. Deliberate, structured research about the domain, that Claude researches for me, BEFORE I wrote a single project instruction.

Research first. Behavior second. Every time.

Past-Andy thought this was “extra work.” Present-Andy would like Past-Andy to know that building twenty useless projects is significantly more work than doing research once.

2. Put Your Research IN the Claude Project Instructions (Not in Attached Files)

This one I discovered completely by accident.

I had been attaching research documents to projects like a responsible person. “Here’s the context, Claude. It’s in the files. Go read it.” Very organized. Very logical. Very much not working as well as I expected.

Then one day, out of laziness or impatience or whatever you want to call it, I just pasted my research directly into the instructions field. Mixed it right after the behavioral rules.

The outputs immediately got richer. More consistent. More… informed.

Here’s what I think is happening: the instructions are the first level of context Claude processes. They’re the foundation. Attached files are important, but they’re secondary. When your research lives IN the instructions, it’s not just available — it’s foundational. Claude isn’t referencing your research; it’s operating FROM your research.

It’s the difference between giving someone a manual to consult and actually training them on the material. Both can work, but one produces consistently better results.

I now treat the instructions field as sacred ground. Domain knowledge goes there. Behavioral rules go there. Everything Claude needs to understand the world of this project — right there in the foundation.

3. “All Over the Place” Outputs Are a Restart Signal

You know that moment when you’re using a project and the outputs feel… inconsistent?

The structure changes between uses. The tone shifts. Claude seems to interpret what you’re asking for differently each time. You start adding more instructions trying to fix it, which somehow makes it worse.

I’ve learned this is a signal. And the signal is: Start Over!

When outputs are all over the place, the problem isn’t that you need more instructions. The problem is that your outcome isn’t clear enough. You’ve built a project that could reasonably produce multiple different things, so Claude — doing its best — produces multiple different things.

The fix isn’t patching. The fix is getting ruthlessly specific about the ONE outcome you want. What exact thing should this project produce? What should it look like every single time? What’s the structure, the format, the tone that NEVER varies?

I’ve rebuilt projects from scratch multiple times when I hit this wall. It feels inefficient in the moment. It’s significantly more efficient than fighting with a project that’s fundamentally confused about what it’s supposed to do.

4. The Best Projects Compound Over Time

My favorite project of all 80 isn’t a business tool. It’s a daily devotional generator.

Here’s what it does: it creates 10–15 minute devotionals optimized for how my brain actually works. It knows my personality framework (ISTP-T, for the Myers-Briggs curious). It knows my faith tradition. It knows I need systematic analysis rather than emotional appeals. It knows I prefer tactical terminology and measurable applications.

But here’s what makes it genuinely powerful: each devotional builds on the previous one. It references answers I gave yesterday. It tracks themes over time. It stores insights in Project Memory that inform future devotionals.

Five months in, this project knows my spiritual journey better than most people in my life. Not because it’s sentient or magical, but because it’s been accumulating context for 150+ sessions.

This is what separates a good project from a transformative one. Good projects produce consistent outputs. Transformative projects compound. They get better because they’re building on everything that came before.

Not every project needs to compound. But if you’re building something you’ll use daily — especially something personal — design it to remember. Design it to build. Design it to become more valuable over time rather than just equally valuable.

The devotional project has a 12-page instructions document that includes domain knowledge about inductive Bible study methodology, cognitive function theory, and specific formatting requirements down to how Bible verses should be linked. Past-Andy would have called that “overkill.” Present-Andy calls it “why this actually works.”

5. If It’s One-Time, It’s Not a Project

Yesterday I analyzed a CSV file for a client. Uploaded it to Claude, asked for analysis, got useful insights, delivered the work. Super helpful.

Did I build a project for this? Absolutely not.

Because here’s the thing: that was a one-time deliverable. I’m not going to analyze that specific type of data regularly. I don’t need a system for this. I need a conversation.

The reusability test is the simplest filter I’ve found: will I do this exact thing again next week? Next month? If the answer is yes, build a project. If the answer is “probably not” or “maybe once more,” just use chat.

Projects are for patterns. Chat is for one-offs.

I wasted a lot of early energy building projects for things I thought I’d do repeatedly but actually did once. Projects that I used for two clients then never touched again. Others for a type of proposal I write maybe twice a year. And one for a meeting format that changed three weeks later.

Now I wait. I notice when I’m doing the same type of task repeatedly. THEN I build the project. Not before.

The projects I actually use are boring, obvious, and embarrassingly utilitarian. They solve problems I definitely have, not problems I might theoretically have someday.

The Uncomfortable Pattern

Looking back at 80 projects, the pattern is almost too simple.

The projects that failed were ambitious. They tried to do multiple things. They were built on instructions without research. They were created for tasks I imagined doing rather than tasks I was actually doing.

The projects that succeeded were constrained. They produce one specific outcome. They’re built on deep domain knowledge. They exist because I noticed myself doing the same thing over and over.

Eighty projects taught me that the boring fundamentals matter more than clever tricks. Research before instructions. One outcome per project. Reusability as the filter for what deserves to be a project at all.

It’s not revolutionary advice. But advice you actually follow beats revolutionary advice you don’t.

And if you’ll excuse me, I have a devotional to read. My project’s been waiting since this morning, and at this point, it probably knows I’m procrastinating.

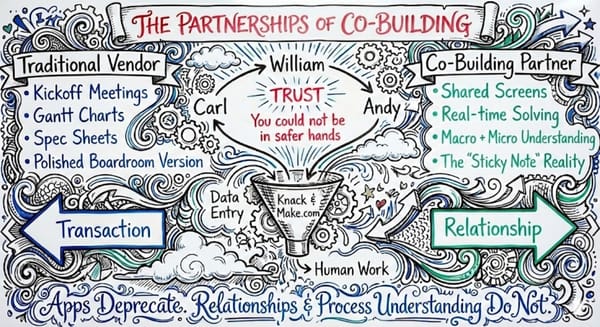

Andy O’Neil helps business owners build AI systems that don’t make them want to throw their laptop into traffic. He’s built 80 Claude projects in four months (the first 20 were “learning experiences”), conducted 700+ co-building sessions, and has a devotional project that knows him better than most humans do. Connect with him on LinkedIn if you want more of… this. Whatever this is.